Disposing of Medications

Donation of medications is not possible for most drugs nor is it available to many people, so you will most likely be looking for a way to dispose of expired and unused medications. Although there are pros and cons for each, take-back programs are the preferred method of disposal. Unfortunately, finding a place to take back medications when you urgently need to do it is limited by an inadequate number of locations and restricted hours of operation. However, there are safe ways to dispose of them at home.

Medicine Take-Back Options

Take-back programs can be used to safely dispose of most types of unneeded medicines, including some potentially dangerous ones. Potentially dangerous medications usually have instructions to dispose of them as soon as they are no longer needed. If a collection center or take-back event is not immediately available, specific directions may call for flushing them down the toilet or sink.

There are generally two kinds of take-back options: periodic events and permanent collection sites.

Periodic Events

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) hosts National Prescription Drug Take-Back events, usually twice a year, where temporary collection sites are set up in communities all over the country for safe disposal of prescription drugs.

- Local law enforcement departments, pharmacies, and hospitals may also sponsor medicine take-back events in your community.

- You can contact your local waste management authorities to learn about events in your area.

Permanent Collection Sites

All take-back sites must be DEA-registered collectors. The location of authorized permanent collection sites vary by community, but may be found in:

- Law enforcement facilities;

- Retail pharmacies;

- Hospital or clinic pharmacies; and/or

- Fire stations.

Some of these sites may also offer mail-back programs or collection receptacles, sometimes called “drop-boxes,” so you can dispose of them yourself.

The DEA Office of Diversion Control Registration Call Center may be called at 1-800-882-9539 to find an authorized collector in your community.

For a number of reasons, inhalers cannot be disposed of in a medical waste disposal box, pharmaceutical disposal box, or sharps container.

- The container and contents are considered hazardous waste.

- Trying to empty them will release active medications into the air.

- Canisters are dangerous if punctured, compacted, or thrown into a fire or incinerator. They could explode and cause a fire.

- See: How to Dispose of Inhalers.

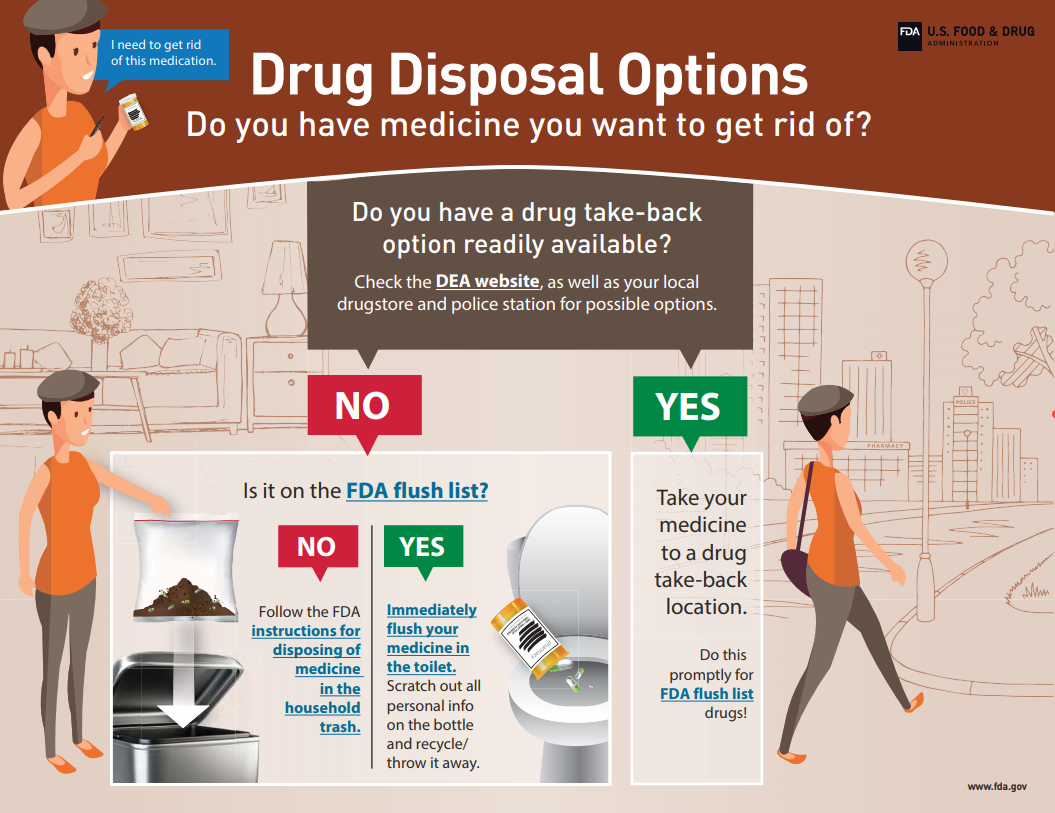

Disposing of Medications Yourself

When no take-back programs, DEA-registered collectors, or take-back events are available in your area when you need them, it may become necessary to dispose of medications at home. There are two choices: throwing them in the trash or flushing them down the sink or toilet. Which of these you choose depends entirely on the medication. You will usually find specific disposal instructions for home disposal of a medicine in the package insert of you OTC or prescription medication.

- They can usually be found in the “Patient Counseling Information” section under Disposal or Storage and Disposal.

- All medications should be disposed of as directed by those instructions.

If this information is not available there are two good sites to look at.

- Enter your medication’s name in the search bar, which will bring up a list of products containing that medication.

- Click on your medication. If labeled ‘Discontinued’ click on another choice that is still prescribed.

- Open the “Labels for NDA xxxx” menu and click on the most recent official package insert.

- Use the Ctrl-F (PC) or Command-F (Mac) to search the insert for “Disposal”.

- Enter your medication’s name in Search MedlinePlus.

- From the page about your medication, which may be the generic name, click on What should I know about storage and disposal of this medication?

- In that section you should find the recommended directions.

Most medicines can be thrown out in the trash and flushing is reserved for few hazardous medications and only if no take-back option is available. The ‘flush list’ is presented in the table below.

- Although it is probably safe to assume your medication can be thrown out if it’s not on the list, it is still better to look, especially if it is not a pill, cream, or lotion.

- Inhalers, such as those for asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or other breathing problems require special handling.

- Liquid medications in glass vials or other sealed containers may also need to be handled differently, so you should check before discarding those.

- You may need to contact your local trash, recycling, and hazardous waste facility or to see if they will take inhalers or sealed glass containers.

In addition to checking the specific directions for disposal, take time to learn the local regulations and laws for your area.

Disposal in the Household Trash

If you can’t take your medications anywhere, you may dispose of most of them in the household trash.

Unless trying to dispose of an inhaler or sealed glass container, you can usually follow these steps.

- Take the medication out of any container, tube, or packaging.

- Mix the medicine as is with a bad tasting substance such as dirt, cat litter, or used coffee grounds. Do not crush tablets or empty capsules.

- Place the mixture in a durable container, such as a sealed plastic ziploc bag or capped plastic bottle.

- Throw the container in your household trash.

When your containers are empty, delete all personal information on the prescription label of empty pill bottles or medicine packaging before you dispose of them.

Mailing in Medications

If you can’t dispose of these medications in the trash, the EPA recommends the drug mail-back option. The envelopes come postage-paid, are pre-addressed to an incineration facility, and can hold up to 8 oz. of consumer/household generated medications in tablet/pill, liquid, or cream form.

- This includes prescription drugs and over-the-counter medications and supplements.

- DEA schedules II-III controlled substances, such as those on the flush list, may also be accepted by some programs.

- Of the total 8 oz. capacity per envelope, up to 4 oz. can be from liquids.).

- They are available online (through ARXG, CVS, and the US Postal Service for example) or for purchase at some pharmacies.

Flushing Medicines Down the Toilet or Sink

Flushing is reserved for dangerous medications, usually opioids, that may be very harmful and, in some cases, fatal if used by someone other than the person for whom they were prescribed. Some may be especially harmful or more deadly to children and pets if taken accidentally.

These medications are too dangerous to keep around the house or even dispose of in the trash, and should be disposed of immediately after they are no longer needed or have expired. The preferred method is still a take-back option, but flushing is Plan B if centers are not available for immediate disposal.

The Environmental Protection Agency opposes flushing. This is out of sync with the FDA, but it’s understandable why. The EPA focuses solely on the environmental impact of flushing, while the FDA also has to consider the safety issues associated with keeping dangerous medications around your house and the limited availability of disposal sites.

Many communities have specific rules about flushing medications. Your local water treatment and/or sanitation department will be able to let you know if yours does.

Potentially Dangerous Medicines Recommended to Be Flushed

A small number of medicines have specific instructions to flush them down the toilet as soon as they are no longer needed, and only if an immediate take-back location or program is not an option.

Links from the brand names in the list below direct you to consumer information about medications which includes specific disposal instructions.

- Once there, type in the medication name and click on search.

- Then click on the label section for that specific medication.

- Select the most recent label and search for the term “disposal.”

Links from the generic names go to detailed information about each medication.

Flushable Medications

Visit the FDA site to view a list of their drug disposal list for certain medications.

Environmental Impact of Flushing Medicines

Many, including the US Food & Drug Administration (FDA) and Environmental Protection Agency, worry about the environmental impact of flushing these medications into septic and sewage systems. However, as you will see, the impact of these medications alone is negligible.

The FDA recognizes their recommendation to flush potentially dangerous medicines raises questions about the impact on the environment and contamination of surface and drinking water supplies. Because of this, studies have looked at this impact and found it to be minimal.

- There are very low, but measurable levels of medicines in surface waters such as rivers and streams, and to a lesser extent in drinking water.

- However, the majority of medicines found in water are a result of the body’s natural routes of drug elimination (in urine or feces) and not from flushing this small number of medications.

The effort to address this concern resulted in the FDA publishing the paper “Risks Associated with the Environmental Release of Pharmaceuticals on the U.S. Food and Drug Administration ‘Flush List’.”

- This paper evaluates the environmental and human health risks associated with the flushing of 15 medicines.

- They concluded that these medicines present negligible risk to the environment, although some additional data would be helpful for confirming this finding for some of these medicines.

FDA has concluded that when a take-back option is not readily available, the risk of harm, including death, to humans from accidental exposure to certain medicines, especially potent opioids, far outweighs any potential risk to us or the environment from flushing them.

The FDA will continue to conduct these risk assessments as a part of larger activities related to the safe use of medicines.

Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs

Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs